Karl Marx’s writings have influenced political thought and activism in many parts of the world – including Myanmar. Hans-Bernd Zöllner uses the occasion of Marx’s 200th birthday to outline how Marxist ideas have been taken up, transformed, and implemented in the course of the country’s history.

The Historical Setting

In August 1938, a Burmese nationalist newspaper, the New Burma, published an article entitled Growth of Political Ideas in Burma. It gave a broad overview on European politicians, philosophers and independence movements – like the Irish Sinn Fein – which had provided Burmese nationalists with models for the Burmese freedom struggle. The article concluded:

“Marxism-Leninism is the new political philosophy for the younger generation, though the elders despise it as something crazy and utopian. ‘Comrades’ and ‘Hammer and Sickle’ come out in the streets, in face of Fascist militaristic organisations of some of our old political leaders.”[i]

One member of the ‘younger generation’ was the then 23-year-old Aung San. Together with other students he had just joined the Thakin Association, the most radical nationalist organisation in Myanmar. The members of this group prefixed the word thakin – meaning ‘master, lord’ – to their names. They, thus, claimed that they were the real masters of the country and not the British commonly addressed with this term.

Another member of the association was Nu, some years older than his friend Aung San, who became Burma’s first prime minister in 1947 following the assassination of Aung San who had been the first commander of the Burmese Independence Army. A third Thakin later became famous under his nom de guerre Ne Win. He had succeeded Aung San as head of the Burmese army in 1943 and toppled Nu’s government through a military coup in 1962. Ne Win supervised Burmese politics until 1988, when a popular uprising ended the ‘Burmese Way to Socialism’ that he had sought to establish together with his military and civilian comrades.

Thus, one can argue that the three men, Aung San, Nu, and Ne Win, who dominated Burma’s politics for half a century, between 1938 and 1988, thus, started their political career as Marxists. This can be explained in light of the anti-colonial struggle against a capitalist country ruled by democratically elected governments. But Marxist political philosophy was more than a fashionable choice of the day.

Marxism, explained in Buddhist terms

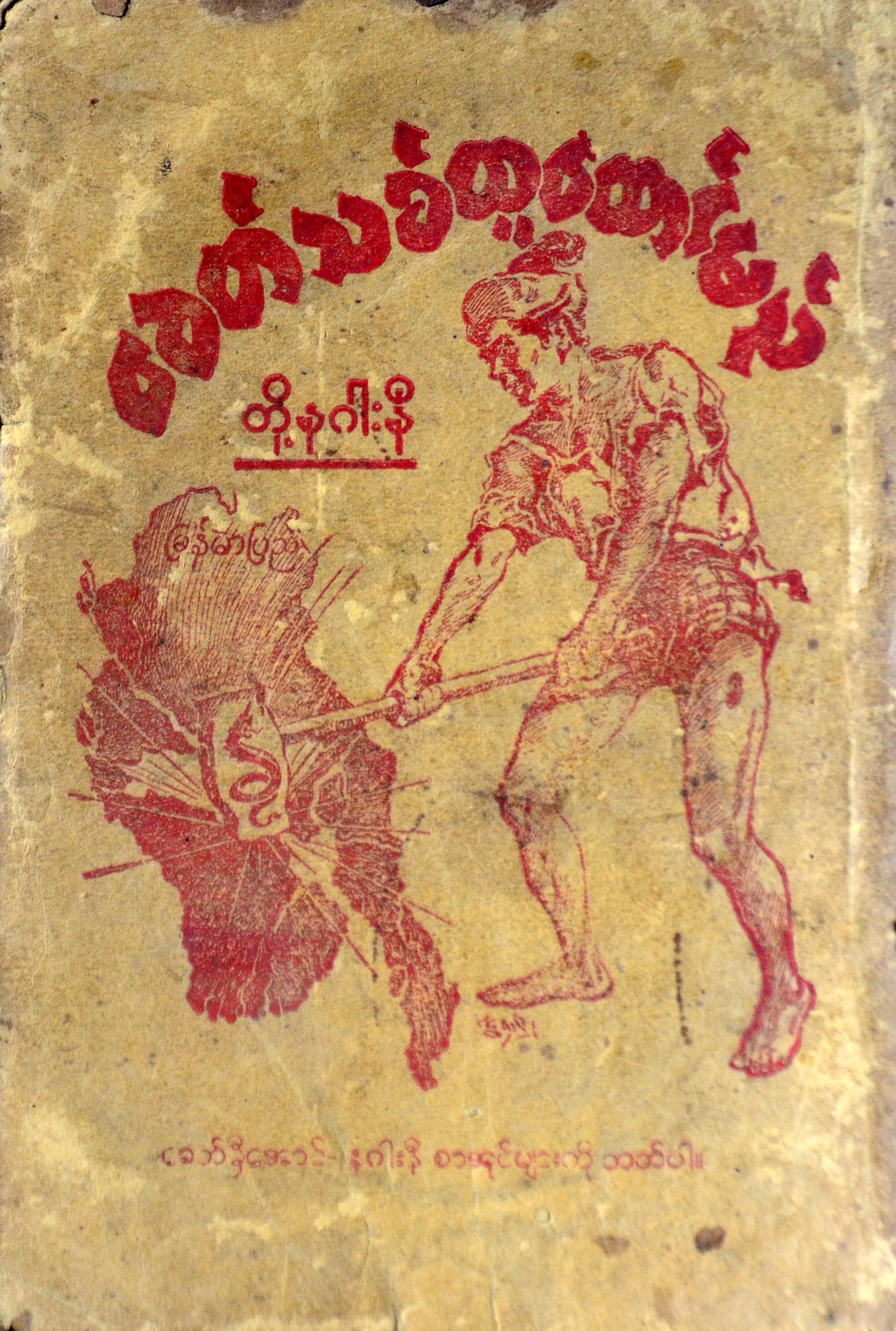

The first books on Marxism came from England in the early 1930s to Burma. They were eagerly read but the language barrier limited the readers’ understanding. In 1938, the first textbook on Marxism was published in Burmese language – written by another Thakin named Soe, with whom Aung San later founded a communist party cell. In contrast to Aung San, Soe had not attended university but worked in Burma’s oil industry.

Thakin Than Tun another ‘master’, wrote the foreword of the textbook and thoroughly discussed the problem of selecting a proper Burmese term for ‘socialism’. No fitting term was found and the foreign word – like ‘democracy’ later – was simply transcribed for the time being. But in order to express Marx’s ideas in a way that would attract Buddhist readers, the author used ideas and terms familiar to the Buddhist audience.

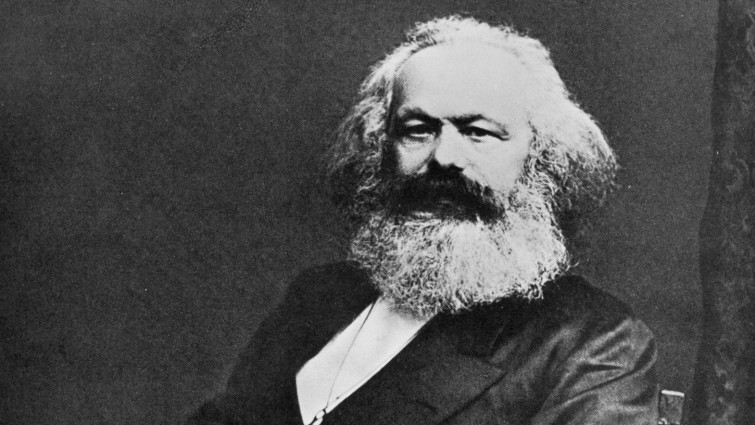

The book described Karl Marx as a poor man who dedicated his life to a higher purpose. He was quoted about his motivation to write The Capital: „To devote myself to this work, I have sacrificed my well-being, my family life and everything.“ The term ‘sacrifice’ was and is used in Myanmar to denote one’s readiness to selflessly give away material goods and even one’s life. Marx was described as, one could say, a ‘secular Buddha’, serving the poor and oppressed worldwide.

On the theoretical level, Thakin Soe explains dialectic materialism by referring to the Buddhist doctrine of Dependent Origination, which elaborates on the causes of individual human suffering and the ways to end it. As a consequence, the convinced communist had to study Buddhist literature in order to introduce socialism to his readers in a way understandable for them.

The divided Marx

Thakin Soe’s book was published by a political book club named Nagani – ‘Red Dragon`. The club was a brainchild of Thakin Nu, conceived on a pilgrimage to Bodhgaya in India, the place where Buddha attained his enlightenment, in 1937. In Calcutta, Nu and a young friend accompanying him met Indian communists who provided them with reading material for their journey. They did not understand the communist textbooks but Nu was fascinated by socialist novels, notably Maxim Gorki’s Mother. Being a writer himself, he conceived the idea of disseminating socialist literature in Burmese language so it was comprehensible for everybody.

The book generation and distribution project was received with enthusiasm by many, but had no solid economic foundation. Shares were sold, to the dismay of Nu’s travel companion, the club’s manager by then. He regarded this way of financing the revolutionary enterprise as a betrayal of Marxist principals, left the club and set up his own publishing house.

Many and more serious splits lay ahead, with different interpretations of how to practice the imported ideology, political competition in the elections organized by the British and personal rivalries all causing rifts. However, during the struggle for independence against the British and later the Japanese enemies, the unity of the Burmese followers of Marx outweighed the differences. A league was formed comprising the army and the emerging socialist and communist parties. Thakin Soe left it in early 1946 because of its alleged compromises with the British, formed his own communist party, and went underground. National hero Aung San expelled Thakin Than Tun – his brother-in-law – together with his followers from the League shortly after, under the accusation of pursuing selfish interests. The expelled party also took up arms after the independence celebrations in January 1948.

Nu in his capacity of prime minister tried to fulfil the socialist legacy left by Aung San with a program to implement a Buddhist welfare state. It was called Pyidawtha – ‘Royal Prosperous Country’ – and combined a planned economy and the voluntary sacrifices of labour and money provided by the citizens. It promised everybody a solid house, a car and a good monthly income and thus an ‘earthly Nirvana’: a popular blend of socialism and Buddhism. The project ended after the ruling League split again in 1958. Nu’s rather soft but popular ‘Buddhist socialism’ was opposed by others who favored a tougher version of Marxism.

When the army took over political power in 1958 on the invitation of Nu (as a consequence of the League’s split), Karl Marx’s legacy in Burma was divided by four. Two communist parties fought underground for a classless society, two socialist parties offered different socialist programs to get the peoples’ vote in the elections of 1960 that ended the military’s interregnum.

The failed great synthesis

Some months before Nu handed over the premiership to Ne Win as head of a caretaker government, he addressed a congress of the still united ruling League with a speech entitled ‘Towards a Socialist State’. He praised Karl Marx as a ‘genius’, whose economic theories were basically correct. A dogmatic interpretation of Marx, however, had converted his teachings into a religious belief system in Burma. As a means to reconcile socialist ideas with Buddhism, he referred to the basic moral principles of popular Buddhism as the only way to win the trust of the people, quoting a story from a previous life of the Buddha. Socialism and Buddhism were thus merged, with the latter coming first. Nu won the elections organised by the military-led government in 1960 with the promise to make Buddhism the state religion.

Two years later after Nu’s election victory over the other wing of tha League, the military ended party controversies and split stories in March 1962 with a coup. Parties were abolished and the setup of a socialist cadre party begun. Its policy was based on a philosophy drafted by former students of Thakin Soe, whose book was often republished. Neither Marxism nor Buddhism was directly mentioned in the document, but Marx as well as Buddha were godfathers of the ‘Burmese Way to Socialism’. A great synthesis of Marxist dialectics and the Buddhist ‘Middle Path’, aimed at starting a permanent revolution in accordance with a basic principle of Buddhist thinking: the law of impermanence (anicca). Party members were exhorted not to take the ideology and programs of the Party to be final. The philosophy’s last words underline the Buddhist motif of sacrifice: “Man to work during his life-time for the welfare of man in brotherhood is indeed a beatitude.”[ii]

Conclusion

The great socialist synthesis finally collapsed in 1988, due to economic mismanagement and an ineffective political bureaucracy. In the same year, Aung San’s daughter proclaimed another loanword – democracy – as the foundation of a new Burma; one that had yet to be successfully synthesised with Burmese Buddhist thought. The legacy of Karl Marx has faded away in present-day Myanmar, the metamorphoses of his ideas remain as a reminder of the tasks lying ahead if a functioning political and economic system is to be established – rather than the simple proclamation of a new Buddhist utopia.

[i] New Burma 28.8.1938 (pp. 3)

[ii] The Burma Socialist Programme Party, 1963, The System of Correlation of Man and His Environment. The Philosophy of the Burma Socialist Programme Party. Rangun. (pp. 39).

Article has been published with permission of the Goethe-Institut Jakarta.

Hans-Bernd Zöllner ist Theologe und Südostasienwissenschaftler und publiziert seit 1993 zu Birma und Myanmar. Einer seiner Schwerpunkte sind die Beziehungen zwischen Myanmar und der Außenwelt.